Shipping Containers: Building Blocks that Disrupt Industries

Paige Welsh | Jan 31, 2018

Paige Welsh | Jan 31, 2018

.jpg)

Today, we can find a “Made in China” label on many—if not most—consumer goods, but this wasn’t the case before the shipping container revolution. When shipping containers dramatically cut the costs of overseas shipping, markets expanded from the reach of a regional trucking route to the entire globe, disrupting not just the shipping industry but the world economy. Shipping containers are now fueling disruption in another large industry: construction.

As Falcon Structures and the Modular Building Institute work to revolutionize the construction industry with off-site building, we remember Malcom McLean, the trucker who pushed containerization into global trade. Offsite construction costs significantly less and cuts building time by 50-60%, yet we still have a long journey to ensure modular or off-site construction is an obvious and popular choice. McLean faced similar challenges in changing the shipping industry, and his story reminds us that when we’re willing to take risks for a dramatically better solution, we can revolutionize the status quo.

Image by Maersk Line (Malcolm McLean at railing, Port Newark, 1957) CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Inertia of the Status Quo

The story goes that while Malcom McLean waited for longshoremen to unload cargo from his trucks, he wondered why he couldn’t just roll his truck’s trailers onto the ships.

Despite this popular narrative, McLean was not the first to notice the short-comings of breakbulk shipping, the practice of shipping freight by the crate or sack load. Several railroads had already experimented with consolidating cargo into large containers that could be moved on and off boats, trains, and trucks, or as we call it today, “containerization.” In the 1950s the United States military created the predecessor to McLean’s shipping containers. The “Container Express,” later shortened to Conex, used 8'6" x 6'3" x 6"10" steel boxes to improve efficiency and prevent pilfering while transporting military supplies overseas.

Conceiving ideas to improve shipping wasn’t the problem; rather, it was convincing people who had grown accustomed to an old, inefficient system to switch to a new technology. McLean ran up against two significant obstacles:

- Generally speaking, the people who had owned and operated the ports had a deep financial stake in the old-way.

- The existing regulatory system, namely the ICC (Interstate Commerce Commission), was wary of McLean’s new approach to shipping.

As Marc Levinson described in his book, The Box, “[In Manhattan] freight transportation was an urban industry, employing millions of people who drove, dragged, or pushed cargo through city streets to or from the piers.” (Levinson, 16)

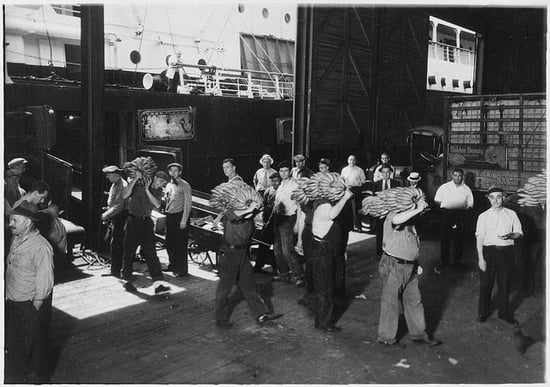

Longshoremen unload bananas from a ship, one stalk at a time. US National Archives.

Longshoremen in particular, had a tremendous stake in breakbulk shipping. Before widespread containerization, longshoremen made a living—if their low wages could be called that—unloading cargo by hand or dolly. In addition to the cost of hundreds of hours of labor, low wages and inconsistent work hours fed a permissive culture of pilfering among longshoremen.

“A common joke at the New York piers was that the dockers’ wages were ‘twenty dollars a day and all the Scotch you could carry home.’” (Bernhofen, El-Sahli & Kneller 2016)

While a longshoremen’s work was grueling and poorly compensated, it was a way of life that supported many port communities. Longshoremen were keenly aware that simply lifting a container filled with tens of thousands of pounds of cargo from a ship to a truck would make of their jobs obsolete.

In 1956, as the Ideal X departed for its first journey as a containership, Freddy Fields, a top official of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) summarized the ILA’s stance on containerization: “I’d like to sink that sonofabitch.”

Port design was also an obstacle. Pre-containerization, the smaller boats and ports were designed to support breakbulk shipping. Renovating the ports to have container terminals and expensive cranes would be no small task or investment. For instance, in 1966 the Massachusetts Port Authority spent $1.1 million (approximately $8.3 million in 2018) to build a container crane. (Levinson, 199)

Breakbulk shipping made most overseas shipping cost prohibitive. Yet, the businesses trying to ship goods, and not the shipping industry, carried these costs. There was minimal incentive for ports to move to containerization unless a competitor forced them to.

The Leap to Containerized Shipping

The legal gymnastics that went into creating McLean’s container-ship business were complex. The ICC, created to check the power of transportation monopolies such as railroad systems, felt a trucking company expanding into the ocean shipping was suspicious. They worried that McLean’s business could grow into a problematic monopoly if not carefully watched.

McLean succeeded in purchasing ocean shipping competitors and their shipping routes, but the ICC did force him to make a risky leap. Simultaneously owning a trucking business and an ocean shipping business was deemed illegal, so McLean sold his trucking business and made the leap to ocean shipping in what some consider the first leveraged buy-out.

McLean’s Impact on Global Trade

With the exception of the Port of Los Angeles, which had discovered highly profitable containerized shipping between Asia and Hawaii, thriving breakbulk ports were reluctant to renovate for containerization. Several small time sleepy ports made way for McLean’s innovation and found new success. Cargo on McLean’s first container ship cost $0.18 per ton to load compared with $6.41 per ton for breakbulk cargo. With a more efficient system a few large ports such as Houston, Los Angeles, Oakland, Port of Elizabeth, and Charleston could handle the nation’s needs. Ports that hesitated to join the container revolution, such as Boston, San Francisco, Gulfport, Manhattan, and Richmond lost their toehold in shipping and had to pursue new economic destinies. (Levinson, 201)

The economic sea change would swell beyond port cities. The shift to containerization had winners and losers. For instance, 70,000 jobs in Brooklyn evaporated with the breakbulk shipping industry. (Levinson, 98) At the same time, as transportation costs plummeted, businesses could set up factories in areas with cheaper land and lower wages; previously job poor small towns enjoyed an economic boost as manufacturing plants left the tight vicinity of port cities.

Containerization also ushered in a new era of global trade. For example, Japanese consumer electronics found a thriving market overseas thanks to lower transportation costs. “Exports of televisions climbed from 3.5 million sets in 1968 to 6.2 million in 1971.” (Levinson, 218) With lower freight costs, the global supply chain became possible. Products were no longer tied to production in one plant, instead factories around the work can specialize in making one or two components and ship them to an assembly site. Consumer goods became cheaper, improving quality of life for many.

A study on the economic impacts of commercial containerization found that shipping container adoption lead to a 320% increase in global trade in its first five years and then a 790% increase in its first 20 years. Economists generally agree that containerization and the expansion of global shipping has been a positive economic improvement.

As Falcon Structures brings shipping container-based construction into the public’s consciousness, we think about how disrupting the construction industry parallels McLean’s endeavor to disrupt the shipping industry. Like the first shipping container revolution, regulators have questions about how to regulate a new practice. Like containerizing shipping, off-site construction is faster, but some people wonder if it’s a gimmick rather than a smart solution. Regardless, we see a reason to be hopeful: if we keep pushing like McLean, word will get out that off-site construction just makes sense.

Thinking about off-site construction for your project? Call us at 877-704-0177 or email at sales@falconstructures.com.

SUBSCRIBE

- Shipping Container Modifications

- How-Tos

- Workspace

- Commercial Construction

- Multi-Container Buildings

- Storage Solutions

- Industrial Enclosures

- Bathrooms & Locker Rooms

- Oil & Gas

- Climate Control

- Green Building

- Industry Insight

- Living Space

- Military & Training Facilities

- Water Treatment Solutions

- Energy

THINK INSIDE THE BOX®

WITH OUR BLOG

Get everything from shipping container basics, to detailed how-tos and industry news in our weekly blog. Stay inspired and subscribe!

RELATED BLOGS

Blueprint for Better Workforce Housing: Shipping Container Benefits

Becca Hubert | Nov 13, 2024 | 4 min read

READ MORE

Protecting Field Workers with Climate-Resilient Container Structures

Becca Hubert | Jun 4, 2025 | 4 min read

READ MORE

5 Benefits of Shipping Container Workforce Housing for Remote Job Sites

Becca Hubert | Nov 5, 2025 | 3 min read

READ MORE